Having identified the core value-creation activities that make up a business model, we can start thinking practically about how those activities are going to be carried out, and by whom. In very small businesses the answers tend to be quite easy (and consistent). Really? Just ask an entrepreneur who handles their supply purchases, who manages their accounts, or who deals with customers, and answer is usually: "I do!" (Though I do know several entrepreneurs who maintain several e-mail addresses, phone numbers - and voices - so that they can provide the illusion of being more than a one-person operation!) But almost any business that scales up requires more people, and having more people means having more formal systems for organising their efforts. And just as it is possible for a market need to be met with the help of different business models, it is absolutely possible for those business models to be supported by different organizational models.

Many of you will have seen a tree-like "org chart" showing who in a company reports to whom. But this can be a little deceiving. The actual way the company works in the sense of who does what, and who depends on whom, is not always easy to infer from org charts. So how should one proceed? Personally, I find that a "functional anatomy" approach goes a long way. Indulge me.

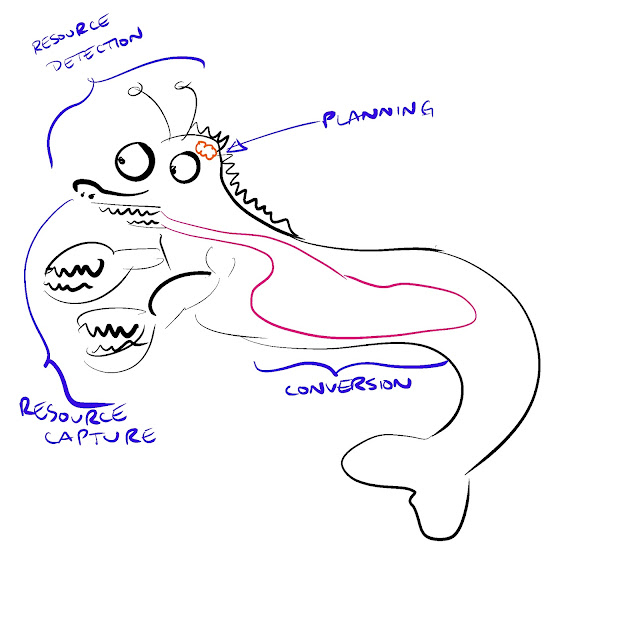

When I think about business, I like the image of a bunch of protozoa evolving their way out of a primordial commercial soup, developing the appendages and organs they need to thrive, and finding their niche in the beautiful, intricate, complex ecosystem of the market. Just as the case in the natural world, there are no rules per se for what an apex predator or a bottom feeder should look like. There are just things that work, and things that don't. And some things, work so well that they just show up again and again.(For example, it appears that paired eyes have evolved several times over, a phenomenon known as evolutionary convergence.)

What follows is the basic functional anatomy of a typical business entity, focusing on those organs, structures and systems that you are most likely to observe.

Eyes, ears, antennae...

Let's start with sensors. Every business organisation needs to be able to detect signals from the outside world. Many people think that a company's marketing department exists only to be the voice of the company, doing things like defining the company's brands and creating advertisements. But in fact, the marketing department is often the home of the company's eyes and ears. It is responsible for studying the market, identifying unmet needs, and identifying the trends that provide clues to future demand. Research and Development, product design and prototyping activites are not strictly speaking "sensing" activities, but they are so closely tied to signals from the market that they should be considered as such.

Claws, paws, mouths and alimentary canals...

Next comes the ability to ingest inputs and extract value. Every business organisation also needs to be able to source materials and transform them into outputs. A company will likely have a sourcing function. For companies that produce goods, that function is sometimes called procurement, purchasing or vendor management. For professional services companies, which deploy teams of people to serve clients, that sourcing functions is effectively the company's recruitment and talent management function, and it is often found inside the human resources department. Having acquired the inputs, the company needs to be able to convert those inputs into the goods and services that serve the customers' needs. If the company sells goods, then the company needs manufacturing and storage. Engineering, production and logistics teams are often loosely grouped under the banner of operations. If you like my functional anatomy approach, you can think of this collection activities as mapping loosely to hands, mouths and digestive systems, all working in harmony. (Except here the output is meant to be more valuable than the input.)

Beyond the basics

So far, we have covered the bare minimum for survival. In organizational terms, a business could function as a few sensing mechanisms connected to production system. But just as in the natural world, such simple arrangements are unable to scale. Organizations that are just eyes, ears, hands and digestive tract are a little like a small business owned and operated by a single team or person. But as a business starts to scale, it needs a more complex system to support it. Finance, human resources and legal can be analogized to the lungs, heart and other organs that allow a creature to engage in slightly more sophisticated behaviours. What goes with this is is a rudimentary coordination mechanism, that we can analogize to the autonomic nervous system. Traditional small-scale industries sometimes follow this pattern, where there are multiple inputs and production steps, and a limited amount of market sensing, but there is limited capacity for further scaling or experimentation.

In order for a business organization to engage in longer-term planning, deeper learning, and more radical reinvention we need a more sophisticated set of structures. The last element of my functional anatomy approach is to analogize the various higher-order business capabilities to the activities of the frontal lobe of the human brain. There are three activities that I would want to highlight. The first is administration of a complex organization. Just as the brain has to synthesize signals from inside and outside the body, so management has to make sure that all the pieces of the organization are acting in sync with each other and in accordance with what the market requires. Depending on how the business is organized, you might find these activities being led by the CEO, the COO, a chief of staff, or another senior manager.

The second, intimately related activity is measurement. To optimize the performance of the business, management needs to not just receive and synthesize data, but do so in some sort of objective, rational, systematic way. Developing metrics, driving business performance with the help of those metrics, and communicating the health of the business to the outside world using those metrics, are all key aspects of management. Measurement activities might be housed in a dedicated business performance function, under a key production or operations manager, or potentially in the planning and analysis department within the finance function.

Finally there is strategy, which involves not just thinking about the business as it currently exists, but also the business as it could one day be. Strategy is the purview of senior management, and ultimately the prerogative of the owners of the company. Though there may be a strategic planning department (which may rely on inputs from finance, operations, sales and elsewhere), strategy is often decided by the CEO and the Board. Because it is a sensitive topic (changes in strategy often create winners and losers within the power structure of an organization), the CEO and Board often work with external consultants to develop or validate potential courses of action.

So what?

Alright, now you have a generic map of what makes up a business. Now, how do you use it? There are a few different ways. The simplest way is to be able to pinpoint who you are really dealing with, within the client's organization. As a business lawyer you are almost certainly going to be working on corporate, commercial and regulatory matters. But all of these matters impact a specific dimension of your client's business. So even if the company's General Counsel is the person who assigned the matter to your firm, that General Counsel is solving a problem for his or her internal client within the business, and that internal client is effectively the one you should care about. Timelines, risks and resources allocated will all depend on which part of the business you are dealing with, and the better your understanding of where a matter originated, the better you will be able to anticipate your clients' needs.

The next level down is understanding the underlying commercial implications of the matter you are working on. It's very cool to be able to say "the management of client X has asked us to advise on a huge asset purchase" but it's smart and useful to know what role this asset plays in the business. Buying a 40,000 square foot commercial site can seem - on the surface - to just be a fixed asset. But whether that site is used for R&D, manufacturing, storage, or as a showroom, has a bearing on how valuable it is to the company, who it can be sold to, and how quickly it needs to happen. Similarly, resolving an employment contract issue can appear to be a generic HR issue, but the implications are vastly different if it affects the company's sales force, engineers, or factory workers.